奇妙な形をした装置の周りに好奇心旺盛な見物人が集まっている。一見したところ三脚に大きな黒い箱が載せられているようだが、内部では不思議なことに手作りの木製カメラと暗室が一体になっている。

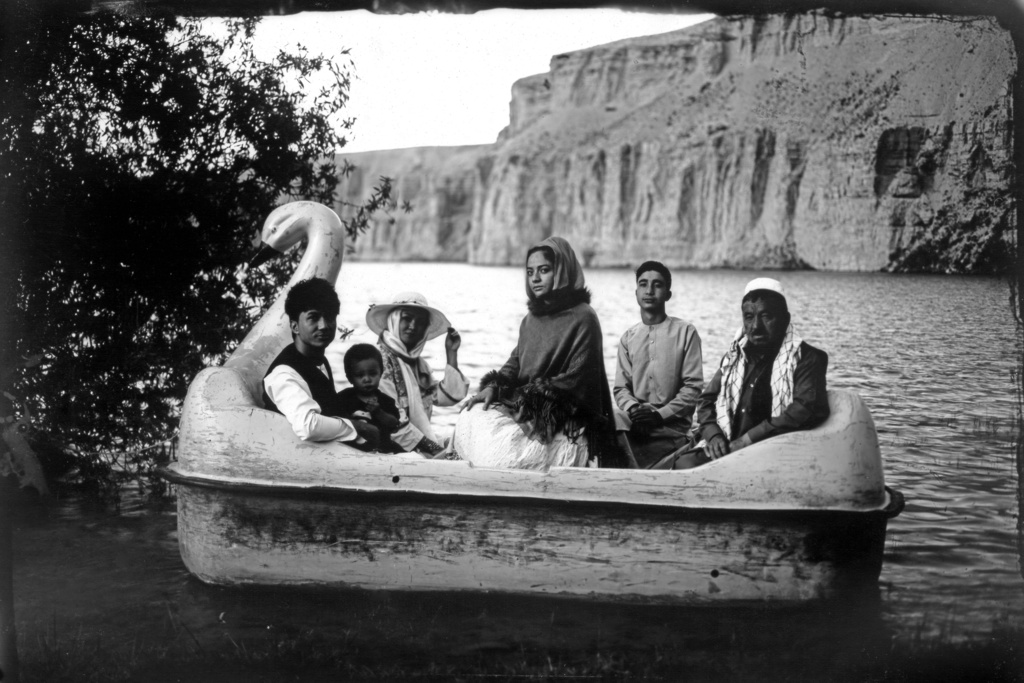

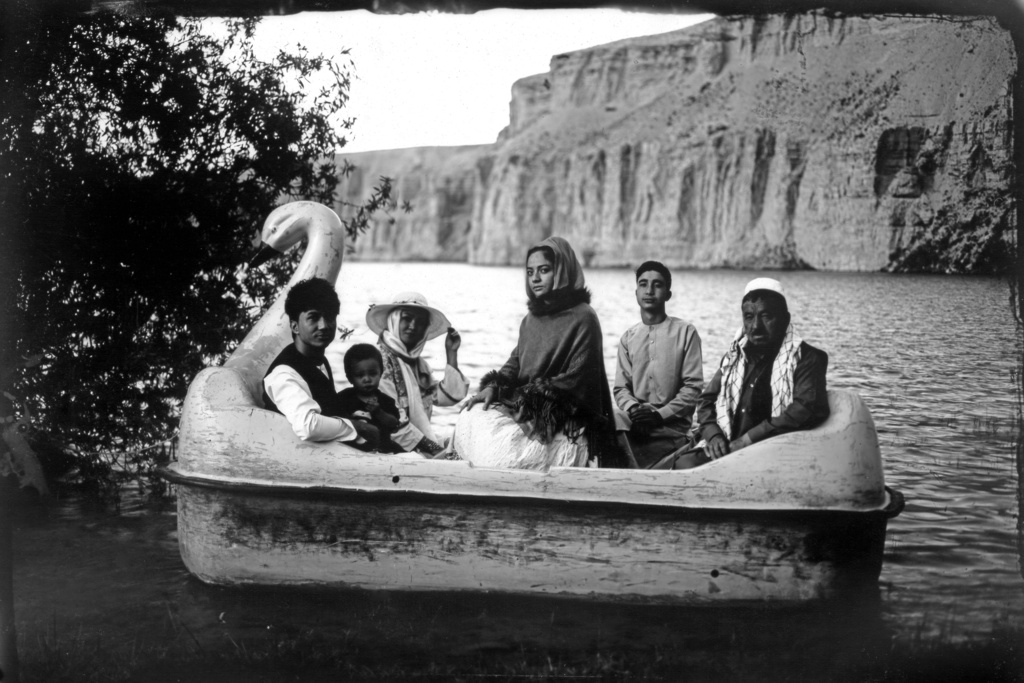

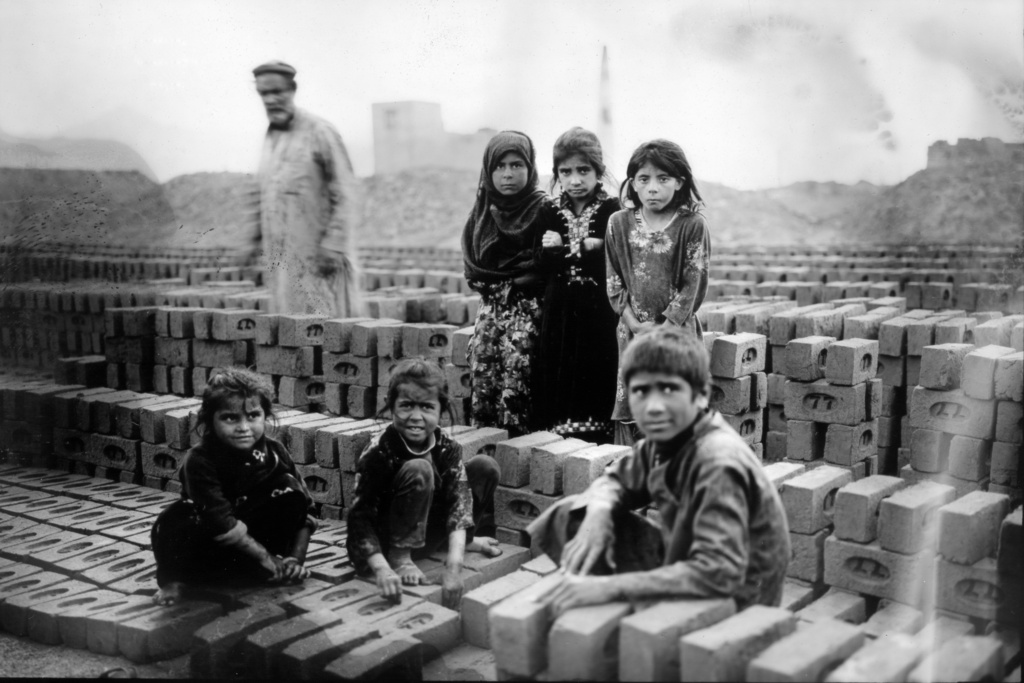

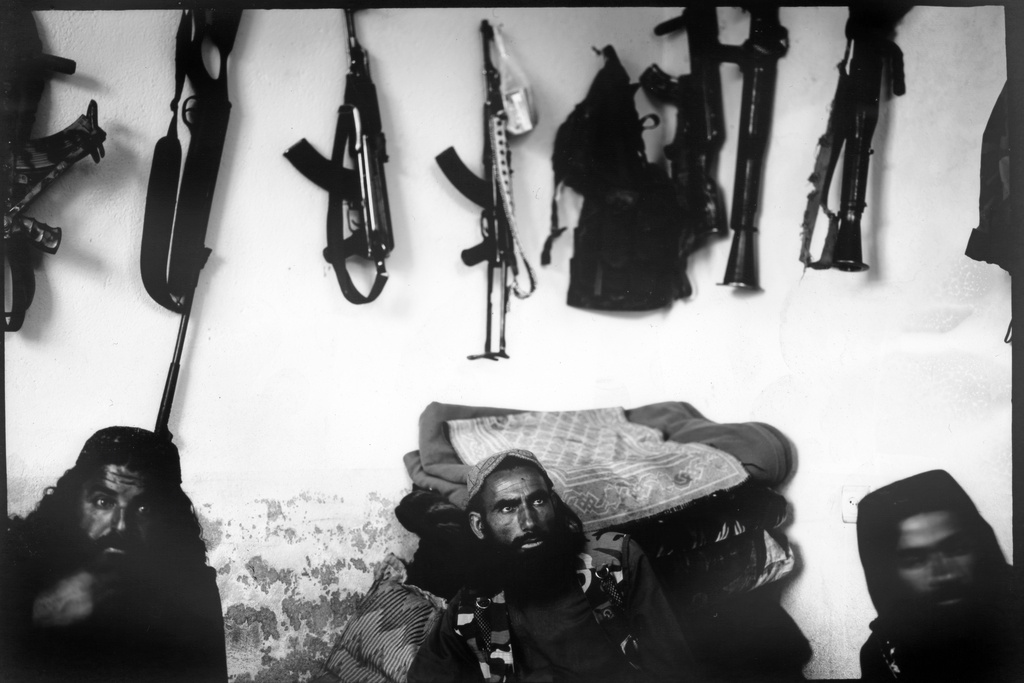

ボックスカメラの周りに人が集まり撮影が行われると、湖でスワンボートに乗り遠出を楽しむ家族、レンガ工場で働く子供たち、全身をベールで覆い隠した女性、目に炎を宿した若い兵士など、カメラの暗室から人生の美しさと苦しみが次々と生み出される。

- 2023年6月17日。アフガニスタンのバーミヤン渓谷地域の観光名所、バンディミール湖で小さなボートに乗って写真を撮るモラディ一家。AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

- 2023年5月30日。アフガニスタンのカブール郊外で、両親とともにレンガ工場で働く子供たち。AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

- 2023年5月29日。カーペット工場で働くハキメさん(55歳)が娘のフレッシュタさん(16歳)に抱きしめられる。AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

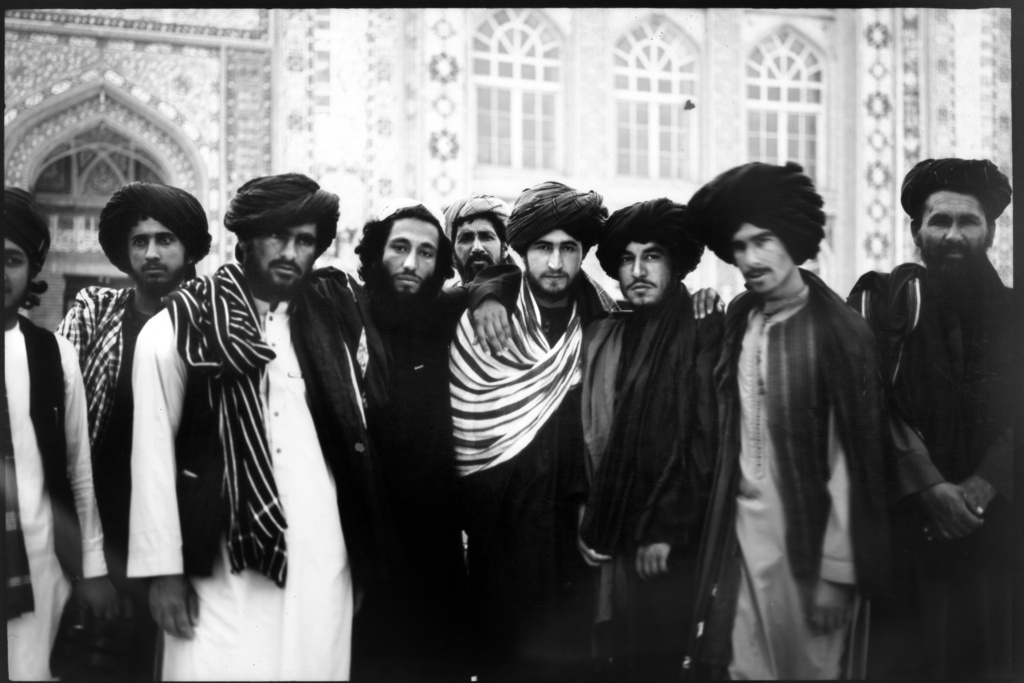

- 2023年6月22日。日干しレンガの家に昼食前に集まるタリバン戦闘員たち。AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd

- 2023年6月2日。アフガニスタンのヘラートで金曜礼拝中、大モスクとしても知られるジャマ・マスジド・モスク内で祈りを終えた宗教学校の生徒たち。 AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

イスラム主義組織タリバンの戦闘員は、戦争の被害を受けたアフガンの村での撮影に際し、「生活が楽しくなった」と話していた。ところが首都カブールで性別を理由に教育を受けられなくなった若い女性は、「私の人生は囚人とか籠の中の鳥のようだ」と言う。

人々の生活の一コマを記録するために使われているのはカムラ・エ・ファオリー(インスタントカメラ)だ。身分証明用の写真を手軽に作ることができるため、20世紀には街角でお馴染みの機械だった。今世紀のデジタル技術の出現によって時代遅れの代物になってしまったが、王政の時代から共産主義政権、外国からの侵略期から反乱期まで、アフガンの半世紀にわたる激動の時代にも、仕掛けが単純で安価、持ち運びが可能なこのカメラは生き残ってきた。

2023年5月29日。アフガニスタン・カブール郊外の自宅でポートレート写真を撮る街頭写真家のルトフラ・ハビブザデさん(72歳)AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd)

戦後のアフガンの生活を記録にとどめるため、西はヘラート、南はカンダハール、東はカブール、中部ではバーミヤンを舞台に、消滅間近とされる同国の芸術形式を用いて、複雑で、時には矛盾したストーリーを映し出す何百枚ものモノクロ写真が制作された。

1ヶ月ほどの間に撮られた写真を見ると、アメリカ軍が撤退し、タリバンが政権に復帰してからの2年間で多くのアフガン人にとっての生活は劇的に変化した。一方で政権交代があったにもかかわらず、数十年間ほとんど生活が変わっていない人もいる実態が改めて浮き彫りになった。

過去の産物になってしまったボックスカメラは、古くて価値があり時代を超越した何かを映し出しているが、まるでこの国の過去が現在に重ねられたようだ。そしてある意味、これは現実なのだ。

一見したところ色あせたモノクロ写真、時には少しピントがずれた写真が伝えてくれるのは、時が静止したアフガンの実情である。その美学は欺瞞に満ちているが、それでも、この国の現状を反映している。

2023年5月28日。アフガニスタン・カブールの全景。AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

カメラとの落ち着かない関係

タリバンは1996年から2001年まで最初に政権の座にあった時代、イスラムの教えに背くとして人や動物を写真に撮ることを禁止した。アフガンのカメラマンによると、多くのボックスカメラが壊されたものの、一部は密かに破壊を免れた。だがデジタル時代が到来し、旧式カメラにも終わりが見えたようだった。

かつてカブールでインスタントカメラの撮影をしていたルトフラ・ハビブザデ氏(72)は、「そのようなカメラはどこかに行ってしまった。デジタルカメラが出回り、旧式カメラは使われなくなった」と話している。やはり写真家だった父親から譲り受けた前世紀の遺物である古いボックスカメラを今も手元に残している。もう撮影はできないが、赤い革でできたコーティングを大事に保存し、サンプル写真で飾っている。

アフガンの街角では現在、顔面を表に出すことを禁止する規則を遵守するため看板広告の顔はスプレーで塗りつぶされ、アパレル店のショーウィンドウに陳列されているマネキンには黒いビニール袋が覆われている。

ところが、インターネットとスマートフォンが出現したことで、写真の撮影を禁止すること自体ができなくなった。新たな規則を取り締まる側の人でさえ、旧式のボックスカメラがみせる斬新な光景を目にすると、興奮と好奇心を抑えられない様子だった。歩兵や政府高官など多くのタリバン関係者がボックスカメラでの前で嬉々としてポーズをとっていた。

2023年6月19日。アフガニスタン・ワルダック州の臨時検問所で写真を撮るタリバン戦闘員たち。AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

カブールのとある倉庫では、カメラが組み立てられるのを真剣な眼差しで眺める男たちがいた。最初は恥ずかし気な様子だったが、最初の写真が出てくると好奇心が勝るようになった。ほどなく冗談を言いながら笑顔で撮影の順番を待ち、背後の黒い布が囲いから滑り落ちそうになると手助けしてくれた。一人ずつ一歩前に進むと、緊張した笑みから一転、顎を引き締めて撮影されるのを待つ。突撃ライフルのグリップを調整しながらも、カメラの小さなレンズをまっすぐ見つめて姿勢を保っていた。

10~20代前半でタリバンに入隊した兵士の大半は戦争のことしか知らない。彼らが原理主義運動に傾倒するようになったのは熱烈なイスラム教への信仰に加え、横行する汚職や犯罪を取り締まることができなかったアフガン政府を20年にわたり支持してきた侵略者、アメリカ軍とNATO軍を追放しなくてはならないという使命感だった。

黒いターバンを巻き鋭い水色の瞳を持つタリバン兵のバハドゥル・ラハニ氏(52)は、タリバンの政権復帰を歓迎しており、「アフガニスタンは再建されるだろう。タリバンなしでは再建は不可能だ」と話している。

- 2023年5月29日。カーペット工場で仕事の休憩中のザーミンさん(32歳)。3人の子供がいる。彼女の夫は5年前にタリバンによる自爆攻撃で死亡した。AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

- 2023年6月3日。アフガニスタン・ヘラート郊外の小麦畑での作業の休憩中にポートレートのポーズをとる18歳のシャハラムさん AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

- 2023年6月7日。アフガニスタンのカブールでポーズをとる交通警察官ムハマド・ヤシーン・ニアジさん(27歳)。彼の月給は1万2000アフガニ、約142USDだが、彼と家族にとっては十分ではないと語る。AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

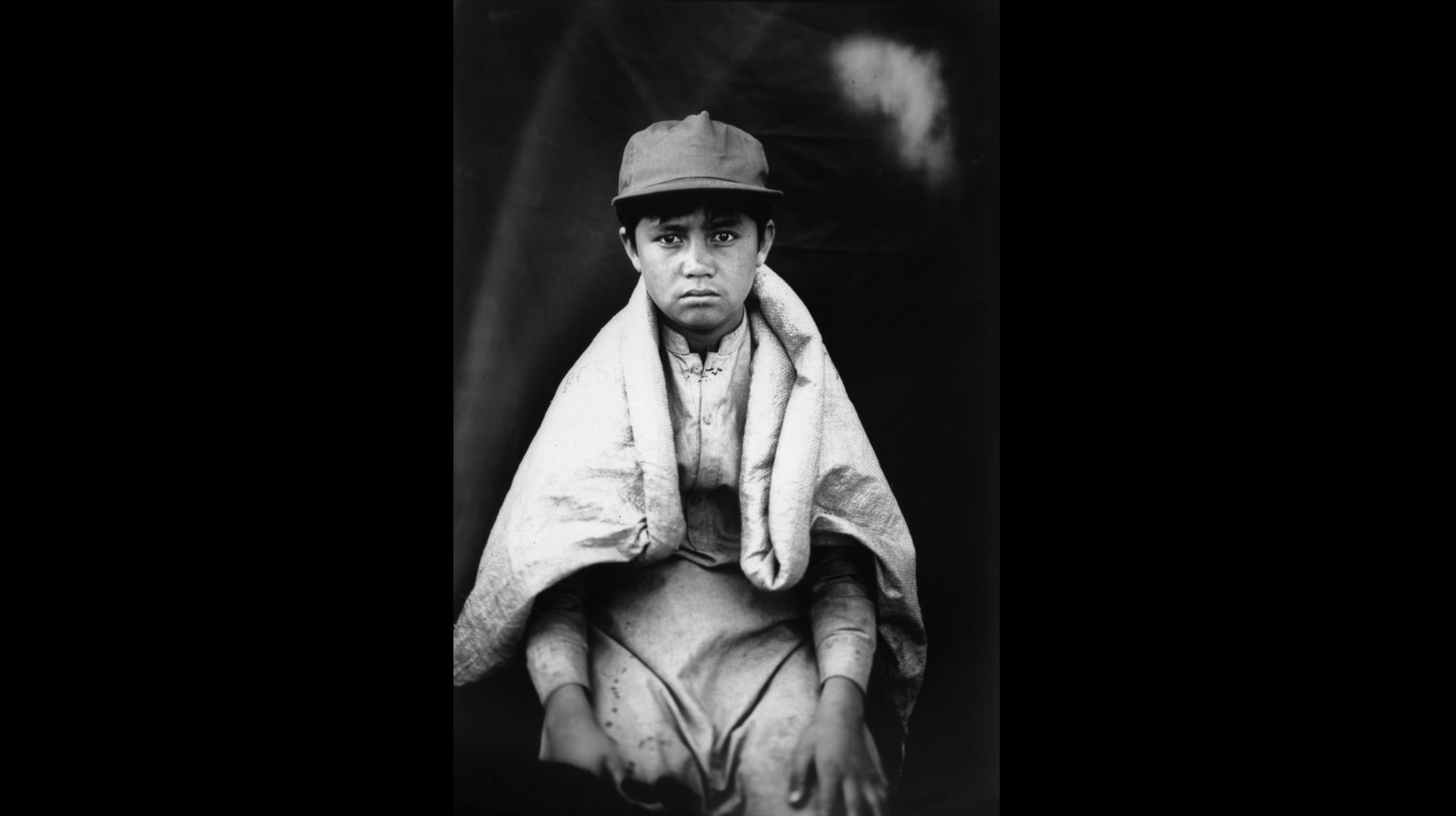

- 2023年6月8日。アフガニスタンのカブールでポーズを取るミルワイス君(11歳)。彼はプラスチックや瓶を集めて首都で販売し、1日100アフガニ(約1.14USD)を稼いでいる。 AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

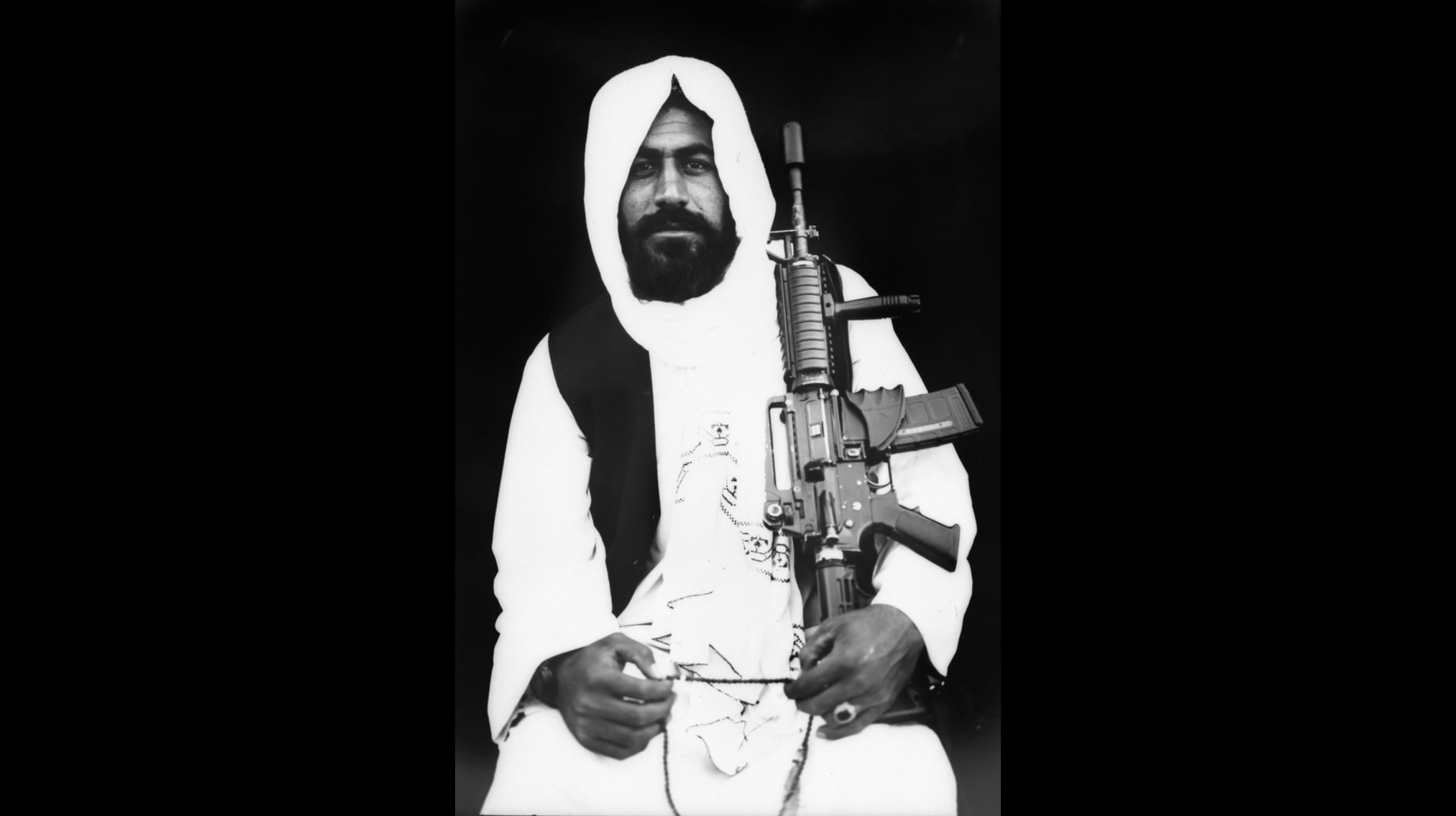

- 2023年6月7日。アフガニスタンのカブールで写真撮影のために座る26歳のタリバン戦闘員ムジーブラフマン・ファケルさん。AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

平和の代償

タリバン兵がアフガン中を席巻し、再び政権の座についてから2年が経った現在は、アメリカ主導のNATO軍がタリバンを01年に政権から引きずりおろす前の生活が色濃く反映されている。

この国は再び、90年代に課された多くの厳格な規則を復活させた原理主義運動に支配されるようになった。最初のタリバン政権は、バーミヤンの崖に彫られた巨大な古代の仏像をはじめとしてイスラム的でないと見なされた芸術や文化遺産を破壊したことで評判が悪い。窃盗犯の腕を切り落とし、神を冒涜したとされる者を広場で公開処刑し、姦通の罪で訴えられた女性を石打ち刑にするなど残忍な刑罰を課していた。

そして今回も処刑と逮捕の動きがはびこるようになっている。音楽、映画、ダンス、公演は禁止となり、女性は教育を受けられず、彼女たちは一部の職業を除きほぼすべての公的な生活から排除されるようになった。

原理主義的な政策に回帰したことで、欧米の支援者、援助活動家、交易相手が国外に追放された。貧困レベルが危機的な水準に達しており、これに女性の就労禁止、対外援助の大幅減、国際的な制裁が拍車をかけている。だが、過去40年にわたる侵略、頻発した反乱、内戦によって絶えることのなかった流血騒動がほぼなくなったことについては、多くの人が安堵している。

タリバンが敵対している過激派組織「イスラム国ホラサン州(IS-K)」らによる爆弾テロはまだ散発的にみられるものの、インタビューに答えてくれた人は、ここ数十年の中では一番穏やかだと話す。

国連によると、タリバンが政権を奪還した21年8月15日から今年5月30日までの間に、意図的な攻撃により1095人の民間人が死亡した。これは、アメリカ主導のNATO軍と反乱軍との間で20年にわたり繰り広げられた戦争で命を落とした民間人の数と比べれば格段に少ない。

現政権を忌み嫌う人でさえ、前政権下で横行していた強盗、誘拐、汚職などの犯罪は概ね抑制されていると認める。

だが犯罪や暴力が減少したとはいえ、経済の繁栄や人々の幸福が必ずしも実現されるわけではない。

2023年5月28日。アフガニスタンのカブールで、人道支援団体から配給される食糧を受け取るために列に並ぶ女性たち。アフガニスタンの4,000万人のほぼ半数が深刻な食糧不安に直面している、と国連の世界食糧計画は述べている。 34州中25州で栄養失調が緊急基準を超えている。 AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

消し去られる女性

カブールの路地裏にひっそりと佇む3階建てビルの中に、黙々と機織りに勤しむ女性がいた。ザマロッドさん(20)は素早い手つき、軽快な指づかいで毛糸をさばき、色とりどりの糸を組み合わせて絨毯を作っている。作業を素早くこなし、あまり愛想はないが柔らかな口調で、「私は囚人みたいな生活を送っている。まるで籠の中にいる鳥のよう」と悲しげに話す。

彼女は大学でコンピューターサイエンスを専攻していたが、タリバンは女性が大学で学ぶことを禁止した。子供の頃に母親から教わった技術を頼りに23歳の姉と一緒に絨毯工場で働いている。他の女性たちと同様に、何か発言することで報復を受けるのを恐れて苗字を明かさなかった姉妹は、家庭以外の場所でお金を稼げる数少ない女性である。

タリバンが政権に復帰して以来、最も厳しい変化に直面しているのは女性たちだ。厳格な服装規定を守らなければいけないほか、多くの職種に就くこともできず、さらには公園やレストランに行くといったささやかな楽しみも許されない。中学以上の教育を受けられなくなり、旅行をするにも親族男性の付き添いが必要になった。

女性は事実上、公の場から消されてしまった。

2023年5月29日。カブールのカーペット工場で働く70歳のニクバクトさん。AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

ザマロッドさんはこのような環境にあっても大学卒業の夢を諦めておらず、「希望を捨ててはいけない。いつの日か自由になれるし、きっと自由を実現できる。だから私たちは生きている」と話している。

別の部屋では、ハキマさん(50)が娘のフレシュタさん(16)に機織りの仕方を教えている。娘がいつか医者になってくれることを夢見てはいるが、生計を立てる手段は今のところこれしかない。母親は全身をブルカでまとった姿でポーズをとりながら、「この国は昔に戻ってしまった。一切れのパンを求めて人々は一軒一軒近所を渡り歩き、子供たちは飢え死にしている」と話す。

経済的な自立を失い、公の場や政権における発言力を失った女性からすると時計の針は逆戻りしたと言えるが、国内の保守的な部族地区においては女性に対する期待は都市部と異なり、アメリカ軍やNATO軍が駐留していた時も含め長年にわたってほとんど変化していない。

それでも、多くの人々にとって教育は最優先課題である。タリバンの一部メンバーも含め、全国でインタビューを受けてくれた人は、ほぼ全員が女性に教育を受けてもらいたいと答えていた。女性への教育の禁止は一時的な措置で、高学年の人から学校に戻れるようになると信じていると多くの人は語る。女性を家に閉じ込めておいても国、さらには経済のためにならないというのだ。

カンダハール西部にあるタビン村の教師、ハジ・ムヒブラ・アロコ氏(34)は、「この村には医師や教師が必要だ。アフガンがあらゆる分野で進歩を遂げるには、女性への教育が必要になる」と話している。

国際社会はタリバンの承認を保留し、指導者に対し女性への制限を撤廃するよう圧力をかけているものの、未だにその成果は現れていない。

アフガン南部で起きた運動の起点で、保守的な価値観が根強く残る都市カンダハールでのインタビューで、タリバン政権のザビウラ・ムジャヒド広報官は、「(女性への教育は)アフガンの内政問題であり、外国は介入すべきではない。今は教育再開の時期を探っているところだ。現在は一時的に閉鎖されているものの、この状態が将来も続くことはない」と述べた。同氏は再開時期こそ明言しなかったものの、外国はタリバン政権を承認しない「口実としてこの問題を持ち出すべきではない」と主張している。

2023年6月8日。カブールのカート・サクヒ墓地の墓の隣で、戦いに使われるのを待つ鳥が檻の中に入れられている。AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

勝利した反乱軍

タビン村はアルガンダブ川渓谷の奥深いところにある。そこでは肥沃な果樹園が広がり、カンダハールの砂漠をぬうように灌漑用水路が流れている。

村の周辺には戦争の名残が至るところでみられる。アメリカ軍の戦闘前哨基地があった場所には吹きさらしの爆風壁に地雷や手榴弾のイラストが描かれた警告がスプレーで描かれ、地面には放置されたレーザーワイヤーが絡まっている。爆撃を受けた家屋は廃墟と化した。戦争にまみれた日々から平和で穏やかな生活に適応しようとする若い武装兵がたむろしている。

路上取り締まり、ビル警備、ゴミ収集など、初めて就いた仕事はありきたりの職種だが、統治には欠かせない。戦争をしていた時代と比べると刺激は少ないものの、暴力から解放された安堵感が明らかに見られる。

空爆や銃弾を怖がる必要もなくなった子供たちは用水路で水しぶきをあげてはしゃぎ、濁った水路に橋の上から飛び込んでは大声を上げている。

2023年6月8日。カブールのカート・エ・サクヒ墓地近くのブランコで遊ぶ子供たち。 AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

桑の木の下で日差しを避けていたアブドゥル・ハリム・ヒラル氏(28)も写真に収まると、「生活はずいぶん楽しくなった。以前は残忍で敵意に満ちていたのに。罪のない人々が殺され、村は爆撃を受けた。とても耐えられなかった」と話す。

ヒラル氏は10代のときにタリバンに入隊し、外国人と戦うことが自分に課せられた使命だと信じて疑わなかった。戦争で20人の友人を失い、多くの人が負傷した。父親を失った子供たちを目にすると亡くなった戦友を思い出し、つらい気持ちになる。だが、彼らが犠牲になったのはそれだけの価値があったのだという確信が慰めとなっており、「戦争で命を落とした人たちは、祖国のために身を捧げて戦った。彼らが流した血のおかげで私たちは今生きていて、自由きままにインタビューを受け、イスラム教徒は平和に暮らしている」と話している。

子供から大人まで好奇心旺盛な人がボックスカメラの周りに集まっている脇を村人が通り過ぎるのを見て、「不思議な光景だ。前は外国人と戦争をしていたのに、今は写真を撮ってくれている」と続けて語った。

タリバン兵のムジェブラーマン・ファカー氏(26)は、カブールの穏やかな検問所で警備を担当している。他の多くの人たちと同じように彼も戦争のことしか知らないため、平時の精神状態に慣れるのに苦労しており、「前は命を犠牲にする覚悟をしていたが、今もその準備はできている」と話す。

低迷する経済、生き残りをかけた闘い

アメリカ軍との戦争が終結して以来、アフガンの治安は改善の方向に向かっている。だが平和の訪れとともに経済環境が急速に悪化した。

タリバンが21年に政権を再び掌握すると、アフガンを援助していた国々は資金を一斉に引き揚げ、国外にあるアフガン資産を凍結し、金融セクターを隔離し、さらには経済制裁を課した。

女性の就労をほぼ全面的に禁止した影響もあり、外国からの締め付けによってアフガン経済は息の根を止められた。国連開発計画(UNDP)の推計によると、昨年のアフガニスタン国民1人当たりの所得は20年比で3割減少した。

国連世界食糧計画(UNWFP)も、人口約4,000万の半数近くが深刻な食料不足に直面しており、全34州のうち25州で栄養不良が緊急基準値を超えているという。

2023年5月30日。アフガニスタン・カブール郊外のレンガ工場で働くマルワン君(7歳)。AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

4歳のカスニアさんでさえ、生きるためには必死で働かなくてはいけないことを知っている。カブール郊外にあるレンガ工場で、彼女は小さな手で泥の塊をすくうと、型に入れられる状態になるまで泥をこねる。何度も何度も同じ作業を繰り返しており、その動きは機械仕掛けのようだ。日の出から日没まで週6日、朝食と昼食の短い休憩をはさみながら兄弟姉妹や父親の隣で働いている。この広大な工場では、子供が3歳になったら働き手に出す家族が他にもたくさんいる。

子供と同じく苗字を明かさなかった父親のワヒドゥラさん(35)は、「子供たちが教育を受けてやがては教師、医者、エンジニアになり、国の将来に役立つ人材になってほしいと誰もが願っている」と話す。

家族全員で働いても食費を十分まかなうことができず、商店主のつけで何とかその日暮らしをしている状態だ。3人の息子と3人の娘のうち、末っ子を除いて全員がレンガ作りに携わっている。

父親は、「若い頃は快適な生活、きれいなオフィス、かっこいい車、公園を散歩、国内旅行、ヨーロッパ旅行などを夢見ていたけれど、今はレンガ作りをしている」とつぶやく。その口調に悲痛な様子はみられず、避けられない運命をただ受け入れているようだった。

多くのアフガン人は家具や衣服、靴など身の回りの物を売りに出して生きようとしてきた。

タリバンが映画の上映を禁止すると、ナビ・アタイ氏は生計の糧を失った。70代の頃にはゴールデングローブ賞を受賞した03年製作の映画 「アフガン零年」のほか、十数本のテレビドラマや76本もの映画に出演した彼が今では極貧生活を送っている。

急勾配の路地が入り組んだところにある彼の自宅には家具がほとんどない。増えた家族を養うために市場で売りに出したのだ。愛用だったテレビも例外ではない。

俳優歴42年のアタイ氏ですら失業し、映画や音楽関係の仕事をしていた2人の息子も同じ憂き目にあった。安全な生活が送れるようになったのは喜ばしいことだが、13人もいる家族を養うことができないという。

ゴミ収集でもいいからと地元当局に掛け合ったものの、仕事を見つけることはできなかった。そこで家財を売りに出すようになったアタイ氏は、「もう希望を持てない」と話している。タリバン政権下では、物乞いも刑罰の対象となる。

この1年でアタイ氏は生きる力を失い、頬はこけ、骨格は細くなってしまった。栄光の日々の思い出を語るときでさえも彼の目には一抹の悲しみが宿っており、「昔はいい映画を作っていた。音楽と映画が再び解禁され、国民が協力し合って国を再建し、政府が国民に寄り添って友人や兄弟として互いを受け入れるような時代が来ることを願っている」と述べた。

2023年5月30日。カエスタ・グルさん(57歳)と子供たち。季節限定のレンガ労働者であるカエスタさんは、夏になると他の何千人もの村民とともにやって来る。レンガ工場で働き、その後ナンガルハルに戻り、一年の残りはそこで暮らす。AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

一瞬の華やかさ

カブールの夕暮れ時、結婚式場で光がきらめき、一瞬の華やかさが暗闇を切り裂いた。

景気が低迷しているとはいえ、結婚式場は活況を呈していた。治安が改善したこともあり、裕福な移住者が伝統的な結婚行事を執り行うためにアフガンに帰国した影響が現れている。

この国の文化で結婚式は重要な部分を占めており、数百人、数千人もの客を招待して豪華な式典を開催し、自己破産してしまう人もいるほどだ。

インペリアル・コンチネンタル結婚式場は4年前に建設が始まったものの、新型コロナウイルス感染症の流行とタリバンの侵攻などにより中断を余儀なくされた。その豪華な会場が昨年ついにオープンした。

支配人のモハマド・ウェサル・クアオニ氏(30)は、広々とした華やかなホールで一晩4組の結婚式をこなしており、高級スーツを身にまとった姿で颯爽と現れた。かつてカブール大学で経済学と政治学を講義していた彼は、苦しい経済状況の中でも結婚式ビジネスを繁盛させようとしているが、その道のりは決して容易ではない。

彼は、「経済環境が弱く」、政府の規則や規制が厳しいことが足かせになっていると指摘する。タリバンは増税を目論んでいるものの、相応の税収を上げられるほどの経済基盤がないと言う。

音楽やダンスを禁止しても得られるものはなく、生演奏をするミュージシャンや臨時収入をもたらしてくれるDJも去ってしまったとクアオニ氏は嘆く。結婚式の集まりは男女別になっており、今回ばかりは女性たちにとってささやかな楽しみがある。

女性が集まる部屋ではカセットテープの音楽を流しながら皆が楽しんでおり、クアオニ氏は、規制があろうとなかろうと「したいことがあるのなら、それをすればいい。女性には女性の楽しみがあるのだから」と話している。

カブールから西に800キロ離れたヘラート郊外に住む実業家のアブドゥル・ハレック・ホダダディ氏(39)は別の課題に直面している。

彼が副社長を務めるラヤン・サフラン社では、貴重なスパイスを主に欧米向けに輸出していた。ところがタリバンの政権復帰とその後に続く制裁によって多くの外国人顧客はアフガン企業との取引を躊躇するようになった。繊細なクロッカスの花をむいたり処理したりするのは男性よりも女性の方が適しており、同社は今でも女性を雇用する数少ない企業ではあるものの、外国の反応は芳しくない。

さらに銀行セクターが隔離されているため、アフガン企業の多くは第三国(通常はパキスタン)を経由する以外に貿易を行う手立てがなく、費用の大幅な増加に拍車をかけている。それに追い打ちをかけるように、干ばつの影響によってサフランなどの農作物は壊滅的な打撃を受けた。

ホダダディ氏の会社はもともと増産を目標に掲げていたが、生産量は3年前の半分まで落ち込んだという。

それでも、彼はこの苦しみを耐え抜く決意を固めている。アフガンの傷を癒す最良の方法はビジネスの成功だと信じているからだ。

タリバンが政権に復帰して混乱を極めていた時期、ホダダディ氏は国外逃亡した何万人もの人々と行動を共にしなくてはいけないというプレッシャーを強く感じていた。ビザも持っていたため家族や友人は出国を勧めてくれたが、彼は留まることにした。当時を振り返り、「とてもつらい選択だった。だけど、もし自分が逃げたら、そして才能や教養のある人たちがいなくなったら、誰がこの国を作るのか。この国はいつになったら問題を解決するのか」と自問したという。

2023年6月18日。アフガニスタン遊牧民が組織したキャンプで、息子のアリ・シナ君(5歳)を伴い、薪を集めるハビボラ君(27歳) AP Photo / Rodrigo Abd

*この記事は、2023年5月から6月に撮影され、2023年10月6日にAP通信に掲載された記事です。

—

By ELENA BECATOROS Associated Press

KABUL, Afghanistan (AP)

The odd device draws curious onlookers everywhere. From the outside, it resembles little more than a large black box on a tripod. Inside lies its magic: a hand-made wooden camera and darkroom in one.

As a small crowd gathers around the box camera, images of beauty and of hardship ripple to life from its dark interior: a family enjoying an outing in a swan boat on a lake; child laborers toiling in brick factories; women erased by all-covering veils; armed young men with fire in their eyes.

Sitting for a portrait in a war-scarred Afghan village, a Taliban fighter remarks: “Life is much more joyful now.” For a young woman in the Afghan capital, forced out of education because of her gender, the opposite is true: “My life is like a prisoner, like a bird in a cage.”

The instrument used to record these moments is a kamra-e-faoree, or instant camera. They were a common sight on Afghan city streets in the last century — a fast and easy way to make portraits, especially for identity documents. Simple, cheap and portable, they endured amid half a century of dramatic changes in this country — from a monarchy to a communist takeover, from foreign invasions to insurgencies — until 21st-century digital technology rendered them obsolete.

Using this nearly disappeared homegrown art form to document life in post-war Afghanistan, from Herat in the west and Kandahar in the south to Kabul in the east and Bamiyan in the center, produced hundreds of black-and-white prints that reveal a complex, sometimes contradictory narrative.

Made over the course of a month, the images underscore how in the two years since U.S. troops pulled out and the Taliban returned to power, life has changed dramatically for many Afghans — whereas for others, little has changed over the decades, regardless of who was in power.

A tool of a bygone era, the box camera imparts a vintage, timeless quality to the images, as if the country’s past is superimposed over its present, which in some respects, it is.

At first glance the faded black-and-white, sometimes slightly out-of-focus images convey an Afghanistan frozen in time. But that aesthetic is deceiving. These are reflections of the country very much as it is now.

AN UNEASY RELATIONSHIP WITH THE CAMERA

During their first stint in power from 1996 to 2001, the Taliban banned photography of humans and animals as contrary to the teachings of Islam. Many box cameras were smashed, though some were quietly tolerated, Afghan photographers say. But it was the advent of the digital age that sounded the device’s death knell.

“These things are gone,” said Lutfullah Habibzadeh, 72, a former kamra-e-faoree photographer in Kabul. “Digital cameras are on the market, and (the old ones) are out of use.” Habibzadeh still has his old box camera, a relic of the last century passed down to him by his photographer father. It no longer works, but he has lovingly preserved its red leather coating, decorated with sample photos.

On Afghan city streets today, billboard advertisements have faces spray-painted out, and clothing store windows display mannequins with their heads wrapped in black plastic bags, to adhere to the renewed ban on the depictions of faces.

But the advent of the internet age and of smartphones have made a ban on photography impossible to impose. The novel sight of an old box camera elicits excitement and curiosity – even among those who police the new rules. From foot soldiers to high-ranking officials, many Taliban were happy to pose for box camera portraits.

Outside a warehouse in Kabul, a group of men watch intently as the camera is set up. At first, they seem shy. But as the first portraits emerge, curiosity overtakes their reservations. Soon, they’re smiling and joking as they wait to have their photos taken, pitching in to help when a black cloth backdrop slips off the wall. As each man steps forward for his portrait, set jaws replace tentative smiles. Adjusting their grip on their assault rifles, they look straight into the camera’s tiny lens and hold their poses.

Most of these men joined the Taliban as teenagers or in their early 20s and have known nothing but war. They were drawn to the fundamentalist movement because of their fervent Muslim faith – and their determination to expel U.S. and NATO troops who invaded their country and propped up two decades of Afghan governments that failed to crack down on rampant corruption and crime.

Bahadur Rahaani, a 52-year-old Taliban member with piercing light blue eyes beneath his black turban, says he’s happy to see the Taliban back in power. With them in government, “Afghanistan will be rebuilt,” he says. “Without them, it is not possible.”

PEACE, AT A PRICE

Two years after Taliban militias swept across the country to seize power again, there are strong echoes of life as it was before U.S.-led NATO forces toppled them from government in 2001.

Once more, the country is ruled by a fundamentalist movement that has restored many of the strict rules it imposed in the 1990s. The first Taliban regime was notorious for destroying art and cultural patrimony it deemed un-Islamic, such as the giant ancient buddhas carved into cliffs in Bamiyan. They imposed brutal punishments, chopping off hands of thieves, hanging supposed blasphemers in public squares and stoning women accused of adultery.

Once again, executions and lashings are back. Music, movies, dancing and performances are banned, and women are again excluded from nearly all public life, including education and all but a few professions.

The return to fundamentalist policies has chased away Western donors, aid workers and trade partners. Poverty has spiraled to crisis levels, fueled by the ban on women working, deep cuts in foreign aid and international sanctions. But there is nearly universal relief that the relentless bloodshed of the past four decades of invasions, multiple insurgencies and civil war has largely ceased.

There are still sporadic bombings, most attributed to enemies of the Taliban, the extremist group Islamic State-Khorasan Province, or IS-K. But Afghans interviewed say their country is more peaceful than they’ve known for decades.

The United Nations recorded 1,095 civilians killed in deliberate attacks between Aug. 15, 2021, when the Taliban reclaimed power, through May 30, 2023. That’s a fraction of the annual civilian death toll over two decades of war between U.S.-led NATO forces and insurgents.

Even those who dislike the current regime say banditry, kidnapping and corruption, which were rampant under the previous governments, have been largely reined in.

But less crime and violence does not necessarily translate to prosperity and happiness.

WOMEN, ERASED

In a three-story building tucked in a Kabul alleyway, a group of women work silently at a loom. Zamarod’s hands move swiftly, nimble fingers flitting between strands of yarn as she knots colored wool around them, making a carpet. Her movements are rapid, almost brusque, but her voice is soft and sad. “My life is like a prisoner,” she says. “Like a bird in a cage.”

The 20-year-old had been studying computer science, but the Taliban banned women from universities before she could graduate. Now she and her 23-year-old sister work in a carpet factory, falling back on a skill their mother taught them as children. They are among very few women who can earn money outside the home and, like others, asked that only their first names be used for fear of retribution for speaking out.

Women have experienced the starkest changes since the Taliban’s return. They must adhere to a strict dress code, are banned from most jobs and denied simple pleasures such as visiting a park or going to a restaurant. Girls can no longer attend school beyond sixth grade, and women must be escorted by a male relative to travel.

For all intents and purposes, women have been being erased from public life.

Even in this environment, Zamarod hasn’t given up on her dream of graduating. “We have to have hope. We hope that one day we will be free, that freedom is possible,” she says. “That’s why we live and breathe.”

In another room, 50-year-old Hakima is introducing her teenage daughter Freshta to weaving. It is their only way of eking out a living, though she still dreams her 16-year-old daughter will someday become a doctor. “Afghanistan has gone backwards,” she says, donning an all-encompassing burka to pose for a portrait. “People go door to door for a piece of bread and our children are dying.”

While the clock has turned back for women who’ve lost financial independence and a voice in public life and government, in conservative, tribal parts of the country, expectations for women have always been different and have changed little over the years — even during U.S. and NATO military presence.

Even so, education is a priority for many Afghans. In dozens of interviews across the country, nearly everyone — including some members of the Taliban — said they wanted girls and women to be educated. Most said they believed the education ban was temporary, and that older girls would eventually be allowed back into schools. They say keeping girls and women confined at home doesn’t help the country, or its economy.

“We need doctors, teachers,” says Haji Muhibullah Aloko, a 34-year-old teacher in the village of Tabin, west of Kandahar. Women must be educated “so that Afghanistan improves in every sector.”

The international community has withheld recognition of the Taliban and pressed its leadership to roll back their restrictions on women — to no avail.

“That is up to Afghans and not foreigners, they shouldn’t get involved,” Taliban government spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid says during an interview in Kandahar, the birthplace of the movement in southern Afghanistan and a stronghold of conservative values.

“We are waiting for the right moment regarding the schools. And while the schools are closed now, they won’t be forever,” he says. He won’t give a timeline but insists “the world shouldn’t use this as an excuse” not to recognize the Taliban government.

VICTORIOUS INSURGENTS

The village of Tabin lies deep in the Arghandab River valley, a fertile swath of fruit orchards and irrigation canals cutting through Kandahar Province’s dusty desert.

But around it, the remnants of war are everywhere. The derelict remains of American combat outposts have faded warnings of mines and grenades spraypainted on their wind-blown blast walls. Tangles of abandoned razor wire litter the ground. Bombed-out houses lie in ruins. And there’s the ubiquitous presence of armed young men adjusting from a life of fighting to one of living in peace.

The new jobs — policing streets, guarding buildings, collecting garbage — are the mundane, necessary tasks of governing. It’s less dramatic than waging war, but there is palpable relief to be free of the violence.

Without fear of airstrikes or bullets, children shriek in delight as they splash about in an irrigation canal, leaping into the murky water from a bridge.

“Life is much more joyful now. Before there used to be lots of brutality and aggression,” 28-year-old Abdul Halim Hilal says, sheltering from the blazing sun under a mulberry tree before posing for a portrait. “Innocent people would die. Villages were bombed. We couldn’t bear it.”

He joined the Taliban as a teenager, believing it was his moral duty to fight foreign troops. He lost as many as 20 friends to the war, and more were wounded. He’s stung by the memory of his dead brothers-in-arms when he sees their fatherless children, but he’s comforted by an unshakeable belief that their sacrifice was worth it.

“The ones that were killed were fighting to sacrifice themselves for the country,” he says. “It’s because of the blood they gave that we’re now here, giving interviews freely, and the Muslims here are living in peace.”

A villager walks by, glancing at the gaggle of curious children and adults gathered around the box camera. “It’s so strange,” he mutters. “We used to fight against these foreigners, and now they’re here taking pictures.”

Mujeeburahman Faqer, a 26-year-old Taliban fighter, now mans an uneventful security checkpoint in Kabul. Like many others, he’s struggling to adapt to a peacetime mentality, because all he’s ever known was war. “I had prepared my head for sacrifice,” he says, “and I am still ready.”

A FOUNDERING ECONOMY — AND A STRUGGLE TO SURVIVE

Security has improved since the end of the insurgency against U.S. forces. But with peace came an economy in freefall.

When the Taliban seized power again in 2021, international donors withdrew funding, froze Afghan assets abroad, isolated its financial sector and imposed sanctions.

That squeeze, combined with the near-total ban on women working, has crippled the economy. Per capita income shrank by an estimated 30 percent last year compared to 2020, according to the United Nations Development Program.

Nearly half of Afghanistan’s 40 million people now face acute food insecurity, the U.N.’s World Food Program says. Malnutrition is above emergency thresholds in 25 of 34 provinces.

Struggling to survive is something Kasnia already knows at age 4. In a brick factory outside Kabul, she scoops out a chunk of mud with her tiny hands, kneading it until it is pliable enough for a brick mold. After countless repetitions, her movements are automatic. She works six days a week from sunrise until sunset, with brief breaks for breakfast and lunch, toiling next to her siblings and her father — one family among many in a sprawling factory where children become laborers at age 3.

“Everyone wishes that their children study and become teachers, doctors, engineers, and benefit the future of the country,” says her father, Wahidullah, 35, who goes by one name, as do his children.

Even with the entire family working, there’s often not enough money for food and they live hand to mouth on credit from shopkeepers. Of his three sons and three daughters, all except the youngest one are brickmakers.

“When I was young, my dream was to have a comfortable life, to have a nice office, to have a nice car, to go to parks, to travel around my country and abroad, to go to Europe,” he recalls. Instead, “I make bricks.” There is no bitterness in his voice, just acceptance of an inevitable fate.

Many Afghans have resorted to selling their belongings — everything from furniture to clothing and shoes — to survive.

When the Taliban banned movies, Nabi Attai had nothing to fall back on. In his 70s, the actor appeared in a dozen television series and 76 films, including the Golden Globe-winning 2003 movie “Osama.” Now he is destitute.

His home, tucked in a warren of steep alleys, is now nearly devoid of furniture, which he sold in the bazaar to feed his extended family. Sold, too, is his beloved TV.

After 42 years of acting, Attai has no work. Neither do his two sons, who were also in the movie and music business. Attai is glad the streets are now safe, but he has 13 family members to feed and no way to feed them.

He asked local authorities for any job, even collecting garbage. There was nothing. So he started selling his belongings. “I have no hope right now,” he says. Even begging is now punished by imprisonment under the Taliban.

Over the past year, he has become frail. His cheeks are sunken, his frame thinner. There’s a sadness in his eyes that rarely leaves, even when he recounts his glory days.

“We made good movies before,” he says. “May God have mercy that music and cinema will be allowed again, and the people will rebuild the country hand in hand, and the government will come closer to the people and embrace each other as friends and brothers.”

PINPRICKS OF GLITZ

The shimmering lights of wedding halls cut through the gloom as night encroaches on Kabul, pinpricks of glitz in the darkness.

Despite the economic slump, wedding halls are doing a brisk trade, buoyed in part by wealthier Afghan emigres returning home for traditional marriage ceremonies now that the security situation has improved.

Weddings are a big part of Afghan culture, and families sometimes bankrupt themselves to ensure a lavish party for hundreds or even thousands of guests.

Construction of the Imperial Continental wedding hall began four years ago but was disrupted by the COVID pandemic and the Taliban takeover. The opulent venue finally opened its doors last year.

Manager Mohammad Wesal Quaoni, 30, cuts a dapper figure in a sharp suit as he sweeps through the glamorous, cavernous halls, juggling four weddings in one night. The former Kabul University lecturer in economics and politics is trying to ensure the business thrives amid the country’s economic woes. It’s not easy.

“Business is weak,” he says, and onerous government rules and regulations don’t help. The Taliban are raising taxes, but he says there isn’t enough commerce to support a healthy tax base.

The ban on music and dancing doesn’t help. Gone are the live musicians and even the DJs who would bring in extra revenue, Quaoni says. Weddings are segregated by gender but, for once, there’s sometimes a bit more fun for the women.

Occasionally women and girls enjoy taped music in the ladies’ section. “If they want, they do it,” restrictions or not, he said. “Women will be women.”

Five hundred miles west of the capital, on the outskirts of the city of Herat, businessman Abdul Khaleq Khodadadi, 39, has an entirely different set of challenges.

Rayan Saffron Company, where he is vice president, exports the prized spice to customers, mainly in Europe and the U.S. But the Taliban takeover and ensuing sanctions left many foreign clients reluctant to do business with an Afghan company – even though it’s one of the few still allowed to employ women, whose hands are deemed more suitable than men’s to extracting and handling the delicate crocus flowers.

The isolation of the banking sector has also left many Afghan companies with no way to trade except through a third country, usually Pakistan, which significantly increases costs. Then there’s drought that has decimated crops, including saffron.

His company had aimed to increase their production this year. Instead, their production fell to half of what it was three years ago, he says.

Khodadadi says he is determined to persevere. For him, successful businesses are the best way to heal Afghanistan’s wounds.

In the chaotic early days of the Taliban takeover, Khodadadi felt intense pressure to join the tens of thousands of people who fled, he says. He had a visa and family and friends urged him to leave, but he refused to go.

“It was very, very hard,” he recalls. “But … if I leave, if all the talented people, educated people leave, who will make this country? When will this country solve the problems?”

By ELENA BECATOROS Associated Press

KABUL, Afghanistan (AP)